This post is part of my series on How to Shape Children’s Behavior.

This post is long. I thought about splitting it into three parts, but each section builds on and relies on the rest, so I decided to keep them all together. Thanks for reading!

The other day, a parent asked me for advice on appropriate punishments for their child’s misbehaviors. I don’t think he was thinking too hard about word choice, but it’s a single word that can make a big difference.The way we think about consequences versus punishments has huge implications for how we parent and raise our children. Any person who cares for children needs to know this: every parent, every teacher, every daycare provider.

We all require consequences

The street I live on is not an especially busy one, but every once in a while, I can hear the screech of tires as a car rounds the bend and zooms past our house. I’m not a fan of the speeding, so sometimes I consider how we could slow people down:

The street I live on is not an especially busy one, but every once in a while, I can hear the screech of tires as a car rounds the bend and zooms past our house. I’m not a fan of the speeding, so sometimes I consider how we could slow people down:

- We could put up a speed limit sign. However, I think most people already know the speed limit in a residential area, yet still choose to speed.

- We could take it up a notch and have a “YOUR SPEED” sign added, flashing the driver’s current speed. This would be effective for people who actually intend to follow traffic laws but sometimes are unaware of their speed. Without a police car to back it up, though, it’s about as useful as a speedometer– it simply notifies the driver that they are speeding, but does not result in any meaningful consequences.

- We could add the police car. Occasionally, I do see a police car camping out at a nearby intersection, presumably to catch speeders. Yet people continue to speed after they are gone. I’m guessing that even after receiving a ticket, a habitual speeder will eventually begin exceeding the speed limit again. As the memory and pain of the ticket fades, the tendency to revert to old habits is strong.

- We could have some serious speed bumps installed. The kind that makes you cry out, “OUCH!” if your car gets scraped up, and the kind that will definitely cause you to slow down the next time you come down the street.

Yes. That’s what we need. Some serious speed bumps. Would you continue to go zooming down that street? I know I sure wouldn’t. Once I realized that those bumps were there to stay, consistently scraping the underparts of my car every single time I raced over them, I would slow down and go the appropriate speed.

It’s just how we are as humans. As much as we may generally agree about a set of norms and rules, we are apt to break them from time to time when it is convenient for us or pleases us. Unless there is a consistent and meaningful consequence each time we deviate, we tend to push the limits according to our whims.

Children need consequences

I don’t think it’s that different with kids. Every year, my students and I work together to develop a set of class norms. Out of thirty children, about half of them naturally abide by the norms. It is only natural to keep their hands and feet to themselves, they would never dream of doing anything but speak and listen respectfully, and they seem to have been born with the ability to always remember things like turning in homework and putting their names on papers. Then there are another ten students who find our norms easy to follow… about 95% of the time. Once in a while they are off task or distracting others, but a meaningful look from me is usually enough to get them back on track. At most, a verbal warning is all that is needed to get them in line.

And then there are the 2-5, depending on your class that year. Every teacher knows the 2-5. No teacher ever forgets those 2-5. The 2-5 students who behave as if they never knew a set of norms existed. The 2-5 students who don’t seem to register any meaning in your meaningful looks, who regard verbal warnings as inconsequential, and who only seem to change when their undesired behaviors are consistently met with meaningful consequences.

Perhaps your children are part of the 50% that naturally and easily abide by “the norms” of your household or classroom. If that’s you, be grateful, and carry on. You must be reading my blog for the food. (However, even the most angelic students have been known to behave differently at home in the absence of a class full of peers and a teacher. Perhaps I have something useful to share with you, yet.)

Perhaps your children are part of the 33%: the children who usually have no problem behaving well, but need an occasional reminder to get back in line. Your child’s teacher probably has no complaints, but you’ve noticed at home that they can push your buttons (or their siblings’ buttons) from time to time and you are looking for a way to minimize such behaviors. If that’s you, be grateful, and read on. Hopefully you will find a concept or idea or two here that can benefit you and your family!

If your child is part of the 7-17%, you probably know it. You have already met with the child’s teacher to develop behavior plans at school, your child might have a behavioral IEP (Individualized Education Plan) in place, and/or the report cards have consistently reported that your child “Needs Improvement” in multiple areas of citizenship. If this is you, be grateful for the gift of life you’ve been entrusted with, and read on. I am glad you are reading and researching and looking for ways to help your child! You care and involvement make a tremendous difference, even if it’s hard to see in day-to-day life. I’ve worked with many parents over the years, many of who seemed to feel despair after years of dealing with challenging school behavior. Every year, however, we saw clear growth and improvement. It took a lot of work, but it was so rewarding to see the fruits of our labor at the end of the year. If this is you, then I’m guessing your time at home can be quite a challenge at times and that you are hoping that the rest of my post will change your lives.

I hope it does, too. But of course every family is different, and there is no one-size-fits all cure for these kinds of things. Read other books and blogs and attend parenting workshops and classes. Do your research and consider what might work best for your family. I hope to share my experiences in working with children and offer insight on how I was able to effectively change specific behaviors. With 30+ children (including 2-5 very challenging ones) each day, I had to come up with systems that were practical, realistic and effective. What follows is the thinking behind my method of what I call “graduated consequences” and some ideas for how you might implement it in a family setting.

I hope it does, too. But of course every family is different, and there is no one-size-fits all cure for these kinds of things. Read other books and blogs and attend parenting workshops and classes. Do your research and consider what might work best for your family. I hope to share my experiences in working with children and offer insight on how I was able to effectively change specific behaviors. With 30+ children (including 2-5 very challenging ones) each day, I had to come up with systems that were practical, realistic and effective. What follows is the thinking behind my method of what I call “graduated consequences” and some ideas for how you might implement it in a family setting.

What graduated consequences are not

First, let me be clear about what graduated consequences are not, and why the common scenario of threats and punishments can actually be detrimental to everyone.

Take, for example, a situation where a student is misbehaving and annoying people. The teacher says, “Stop doing that.” The student stops, but later does something else to annoy classmates, so the teacher repeats, “Really, you need to stop doing that!” The student continues acting up, so the teacher threatens, “If you keep doing that, I’m going to send you to the office!” The student stops for a while, but later in the day acts up again. Since a couple of hours have passed, the teacher has cooled a bit and merely repeats the threat, “Do you want to go to the office? No? Then you need to stop!” Again, the student stops temporarily, but later does something else, at which point the teacher finally sends the student to the office.

In a school setting, if I did something similar and threatened punishment until I couldn’t stand it anymore and sent a student to the office for finally “going too far,” this would probably result in a number of undesired results, including:

- A student feeling bitter at a disproportionately strong punishment. They are probably only aware of their last offense, and think that they are going to the office just because of that one thing. They do not see it as a build-up of many offenses throughout the day.

- A student losing out on valuable instructional time while wasting away in the office.

- A student feeling a loss of control over their lives, likely resulting in more chaotic behavior in the classroom in the future; they don’t understand why this time they got sent to the office, and why all the other times they didn’t.

- A loss of trust between us. They don’t trust me to help them or coach them to be better. They just know that whenever I want, I have the power to “get them in trouble.”

- A teacher who has endured a day of dealing with a difficult child.

I have witnessed variations of this situation in classrooms and in families a number of times. A parent keeps telling a child to stop, threatens with a punishment (“If you don’t stop we are going to leave!”), keeps threatening, and either the child stops or the parent keeps threatening punishment (which is an increasingly empty threat the more they say it but don’t follow through).

There are only three ways this scenario can go, and all of them have drawbacks:

1. The child stops the behavior. This is the best of the three options, but is still weak in that a misbehaving child received no consequences for their initial poor choice(s). They are apt to repeat it in the future.

2. The child keeps pushing it, and the parent eventually follows through with the threat. While it is good that the child knows you really will follow through (which gives you more credibility in future instances), it’s likely that it took a few more rounds of warnings before you followed through with the threat. The child loses their sense of control because they did not know at which point you would finally break and give the consequence. The child also feels a sense of unfairness because they had, in a sense, “gotten away with it” the first five times and they don’t know why the sixth time should suddenly be any different and actually result in a consequence. Even though you kept warning them, in a way, they didn’t really see it coming. This sense of lack of control will probably make the child act out even more once the punishment is fulfilled, and that’s no fun for anybody.

3. The child keeps pushing it, and the parent does not ever actually follow through with the threat. This teaches the child that sometimes, you don’t really mean it. It takes away credibility from all of your future threats. In the future, when you actually follow through, they will be even more upset, because they might have thought they could get away with it like last time. Worse, you rarely follow through and the child learns that your warnings are meaningless so your child does not listen to you.

In these instances, any victory is temporary, at best. However, none of these scenarios sets you or the child up well for future instances, and none of them teaches your child anything about actually improving behavior. It just staves off poor behavior for a little while until the next round.

Understanding the difference between consequences and punishment

Merriam-Webster defines punishment as “suffering, pain, or loss that serves as retribution,” and “severe, rough, or disastrous treatment.” Compare this with the definition of consequence: “something that happens as a result of a particular action or set of conditions.” You will quickly see that they are not the same.

Punishments are usually threatened, and then finally given. Sometimes, they are not even threatened– they are just given after the matter. This can be the source of great anger, confusion, and frustration in children. They did not know that there would be this particular punishment (or, in some cases, any punishment) for their actions, and they have no control over what is to follow.

As strange as it sounds, punishments can cause children to be resentful but not necessarily make better choices in the future. Consequences, on the other hand, empower children to make better choices and reduce bitterness and anger when they reap the consequences of their actions. Consequences are about cause and effect. As the consequence-giver, there is little (if any) emotion attached, no anger necessary, and much consistency required. Here is a table to clarify what I think of as some key differences between punishments and graduated consequences as pertaining to children’s behavior:

| Punishments | Graduated Consequences |

| The main goal is to punish someone for a past undesired behavior. | The main goal is to change someone’s future behavior. |

| Punishment is threatened for an undetermined amount of time, then given. | Consequences are immediately administered. |

| The person in charge usually endures a period of increasing annoyance before finally hitting their “limit” and giving the punishment. In other words, they get very frustrated and upset. | The person in charge immediately addresses any inappropriate behaviors with a consequence (however small). Consequently, the person in charge does not have to feel as annoyed. In other words, they do not get very frustrated or upset. |

| Takes time to dole out, and is generally unpleasant. Decisions are often made in the heat of the moment, which increases chances of giving unreasonable, unjust, or unrealistic punishments. | A simple matter of progressing down a series of pre-set consequences. The process is fairly quick, and most major decisions have already been thought out. |

| Child judges whether things are fair/unfair. | Child already understood what would happen next and that this is a natural next-step. They tend to accept consequences without fuming or questioning the fairness. |

| Child feels no control over what will happen or when it will happen. | Child understands what will happen (and they knew it would happen as a result of a behavior choice they made). They also understand why the consequences are happening (which is an important part of changing their future behavior). |

Now that we see that punishments and consequences are different, here are some other crucial things to keep in mind as you consider how you will develop a system of graduated consequences.

What are graduated consequences?

In short, “graduated consequences” are what I call a system of consequences that are increasingly weighty the more a child continues to make poor choices in a day. In my classroom, I set up a system of graduated consequences to address everyday, run of the mill misbehaviors: rolling eyes, messiness, distracting classmates, etc. I found that simply and gently pointing out the boundaries with smaller “nudges” were more effective than jumping to a huge consequence for certain misbehaviors.

If a student makes a poor choice, I would try to give a meaningful look to communicate a wordless warning first. To some students a meaningful look is a consequence. They feel it in their insides as my eyeballs make their hearts race in alarm. I have found this to be sufficient to end ~90% of undesired behaviors in the classroom.

For the 10% that continue, simply telling them to stop is very effective.

For the 10% that continue, simply telling them to stop is very effective.

For the 5% that still continue, then I would officially place them on the “consequence track,” by adding a simple but powerful phrase: “This is your warning.”

Here is my official (graduated) consequence track:

1st consequence: verbal warning, “This is your warning.”

2nd consequence: visual warning, “Pull your yellow card.”

3rd consequence: complete a “refocus form” in another teacher’s classroom. The form must then be signed by parent and returned the next day.

4th consequence: detention

5th consequence: conference with parents and possibly principal.

It’s very effective. I find myself saying, “This is your warning” only a few times a week, and we only get to the yellow cards a few times a year (for the whole class). There is no need to threaten the child with some other impending punishment—they already know what the next step will be if they continue to make poor choices. Even though something happens each time they make a poor choice, they are never surprised, and I believe this gives them a sense of control over their own actions and behaviors.

So let me take you through an example of how it would look to go through the system of graduated consequences. Let’s say it’s reading time in the morning. I notice that one student does not have her book out and is instead playing with her eraser. I give her a meaningful look and she puts it away and takes out a book to read.

Later, during a math lesson, I notice her spinning a pencil on her desk. I walk over and tell her to take out her work and pay attention. She begins to, but several minutes later, I see her throwing crumpled scraps of paper at a neighbor, so I say, “Sienna, stop throwing the paper. This is your warning.” She straightens up, clears her desk, and focuses. Usually, I don’t have to go any further than this to get a child to straighten up for the day (or for the next few weeks, really). But, for the sake of the example, let’s suppose she then begins flicking eraser bits around her desk. I would turn to her and say, “Sienna, clean up the eraser bits and pull your yellow card.” She would clean up, pull her yellow card, and return to her seat. I would remind her to focus, and remind her that the next offense will send her to another classroom to complete a “refocus form.”

Later in the day, after lunch, we’re at the carpet and I see the person behind her ask her to move over to give more space. She not only ignores this request, but she scoots back to take up more of his space. I coolly ask, “Sienna, what just happened?” She knows from my tone of voice that I know exactly what happened, so she owns the truth. I calmly acknowledge her choices, but am firm in the consequences: “Thank you for telling me the truth. That was the right choice, and I’m glad you didn’t try to lie about it or you would have received further consequences. Now please get a refocus form and go to room 26. You can come back when you’re done.” She is not happy about this, but she also knew it was coming. She calmly walks to the back, gets her form, and exits the room. The whole process has been pretty simple and straightforward.

Later in the day, we would meet privately to reflect on and discuss the behaviors. Oftentimes, there is some other trigger underlying the inattention or misbehaviors. Sometimes I cannot find one. However, the graduated system of consequences minimizes opportunities for a distracting student to veer me and the rest of the class off course for more than a few seconds. I can calmly continue with my agenda while still administering consequences to shape behavior. This is especially important in a classroom setting.

The first consequences are relatively small and are enough to help most children straighten up. The children would not be surprised at any point, and they would learn to not argue when given a consequence. Arguing won’t do anything but earn you further consequences (for being disrespectful), and the best way to avoid more consequences is to simply stop the undesired behavior. Children learn surprisingly quickly, if not from their own mistakes, then certainly from watching others.

Once students understand how the system of consequences work (you’ll have to run through it a couple times for them to grow familiar with it first), everything moves more smoothly. The first couple times of using it are more for them to test you out (and see if you really will call them out for “pushing it”). It may seem rather ineffective at first, and you might find yourself thinking, “Hey, I said, ‘This is your warning,’ but she still talked back! This doesn’t work!” In that case, go up the next level and give a consequence for talking back. If she keeps pushing it, work your way through the consequences until she stops the poor behavior or she receives a more serious consequence. Once she realizes you really are following through, the next time you say, “This is your warning,” you can bet she will make a greater effort to control herself and stop the undesired behaviors.

Like I said before, there is no one-size-fits all policy. If I saw these behaviors in a child who usually has great behavior, I would probably talk to him privately and investigate more first to see what the root of the problem is. Usually, I find that something else is going on and respond accordingly. However, for the 2-5 students a year who frequently need reminders of where the boundaries are, this is an effective way to gently but firmly draw the lines in place.

Of course there will be times when something hugely unacceptable (for example, hitting someone) happens, and this isn’t the time to simply say, “This is your warning,” and carry on with the lesson. Those instances need to be handled on a case-by-case basis.

Graduated consequences for the family

Now that we have an understanding of how graduated consequences work, it’s time to think of how this can be used in a family setting. The good news is that you can customize the steps and consequences according to what works for you, and what is meaningful to your children. The bad news is that I am not going to fill in all the blanks for you—every family and every child is different.

However, here are some ideas for how this might work out in the home. First, simply and firmly tell your child to stop the undesired behavior. If it continues, then:

1st consequence: Give a verbal warning, “This is your warning.”

Now your child knows they are “officially on the consequence track.” Once they understand how the system works, this simple phrase will be enough to have them straighten up most of the time. Remember, the first couple run-throughs will probably involve your child testing you to see if you really mean it.

2nd consequence: Give a visual/physical warning, “Bring me _______” (a predetermined symbolic “warning object”).

This is effective in giving your child a tangible way of registering that they need to reset. Sometimes they need to see/feel/hold something to realize they need to change. As your child walks to their room to retrieve the object, it is also an informal timeout for them to pause and think through their actions and hopefully get themselves together enough to stop the undesired behavior.

Some ideas for visual warning objects: a laminated yellow index card, a large popsicle stick in their pencil cup that is painted/colored yellow, a snazzy pencil, etc. It just needs to be something that you can hand them during your initial talk and say, “When I ask you to retrieve this object, it’s your second warning—it means I’m really serious, and you’d better get yourself together or you will receive the next consequence.” The object should have a permanent house, whether it is a specific drawer, the pencil cup, or in their backpack.

You might want to skip this step, depending on the age of your child.

3rd consequence: Complete a refocus form.

It might be something like this.

Again, you might want to skip this step, depending on the age of your child.

4th consequence: Give a timeout.

Have a designated space where the child must remain for a given period of time.

Again, you might want to skip this step, depending on the age of your child.

5th consequence: Take away something that matters to the child and, if possible, is related to the offense.

For example, TV time, dessert, screen time (ipad, computer, smart phone, video games), a week of texting, money, etc.

6th consequence: Lose some other (bigger) privilege.

For example, a month of texting, grounded from social activities, TV for two weeks, etc.

Practical steps to get started

1. Set up your own system of graduated consequences. It can be any combination of the above ideas. Maybe steps 3, 4, and 5 are simply increasing amounts of screen time being taken away (instead of “the object,” a refocus form, and a timeout). Customize it to what is meaningful and age-appropriate for your child. Type it all up clearly and print it.

2. Explain how it works to your child. After going over the 4-6 graduated consequences, I usually do some role-play with my students, and have a volunteer act out a character that keeps “pushing it,” while I play the teacher part. I find that role-playing helps so when the real thing comes, none of it surprises the children. It’s usually easier to prevent problems than deal with them after the matter. They are expected to submit to the consequences, rather than being angry about them.

3. If this is your first time using a graduated system of consequences, then target a single behavior that you want to see improvement in. The goal this first time around is more to learn the system (for both you and your child!), and not as much to change a behavior. Choose something fairly easy for this first time, as learning a new system of how to do things will already be a challenge for both you and the child.

4. Begin immediately with this one target behavior, and be consistent… day after day after day after day. Hold your child to that high standard and don’t let things slide– children have the ability to pick up on that very quickly and might subconsciously “push it” as they feel out how far the boundaries really are. You must be consistent! This is easily the one thing that will make or break the whole system of consequences. The moment your child believes that sometimes you mean it and sometimes you don’t is the moment you lose credibility and power to help her make effective, long-lasting change. This is also a good case for Mom and Dad to get on the same page, because we’re all too familiar with how children can play that game.

5. Apply it more generally to other expected behaviors as you and your child grow more familiar with this system. If, on the other hand, there are behaviors you wish to ingrain in your child (that are not yet “expected behaviors”), consider concurrently using a rewards system to help them develop a good habit.

It can be very wearing at first, but a lot of effort at consistency in the beginning will set the tone for future behavioral endeavors and make everything increasingly easier. The more you get the hang of it, the more it becomes second nature. Once your child understands that “This is your warning” really will be followed by the next consequence if they continue to push, they will begin exercising restraint like never before. They just need to know where the boundaries really are, and you must be consistent in showing them.

Choosing Consequences Carefully

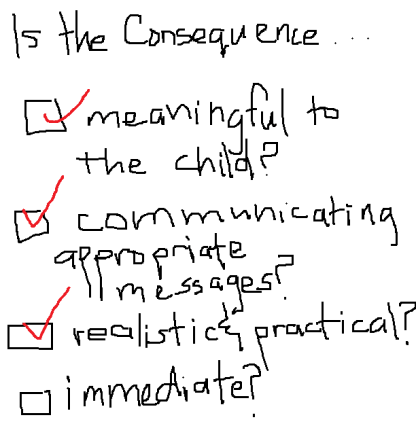

In my classes of 30 children, I had to think carefully about the consequences for my students. They all needed to fit a few criteria, including the following:

- Be meaningful to all students

- Communicate appropriate messages (or at least not communicate unwanted messages)

- Be realistic and practical for me to administer/minimally disruptive to the class.

- Be able to be administered immediately

These criteria are very important things to consider as you develop your own system of consequences. What is “meaningful” or “realistic and practical” will differ from family to family (and maybe even child to child), and you need to think through it carefully.

1. Consequences should be meaningful

You need to make the consequences something that your child cares about. If your child loves to spend time quietly reading in her room, then sending her to the haven of her room for hitting her brother is probably not a very meaningful consequence. If your child is bored at a restaurant and starts acting up, then setting up the consequence of leaving the restaurant might actually encourage poor behavior if the child wants to leave. Find something that matters to your child.

2. Consequences should communicate appropriate messages, or thinking through the consequences of your consequences

First of all, it is vital that you think through what the consequences of your consequences are. Yes, I said the consequences of your consequences. Here’s what I mean. One time, I was teaching at a workshop when a parent proudly shared a story about what she did with her son. Since he was not cleaning up his toys, she threatened to donate all his toys to a local charity if he did not clean up all his toys. The day eventually came when he did not clean up all his toys. True to her word, this mother made the boy pack up his toys, and drove him over to a donation center and made him donate his toys.

One chance. One mistake. And then… bam. All his toys, gone. Even to me, that seemed rather harsh and unjust.

I had to bite my lip to hold back my comments. I think she concluded with something about how he kept his room clean after that, but I couldn’t help but wonder what the consequences of her consequences would be. Sure, a clean room is a nice thing to have, but I would argue that there are more important things to consider, such as how consequences can shape character– for better or for worse. How would this event affect the child’s perspective on giving to charity? Would he forever see it as a punishment rather than a privilege to give to others? Would he see generosity as a trait of the weak, rather than the strong? Hopefully none of these things would happen, but it goes to show that we must think very carefully about the message we are giving with our consequences. Always consider the effect they might have on our children and their character as they grow.

I have also seen children being forced to say sorry to someone. This can give the message that saying sorry is a bad thing: If I say sorry, that means I lose. If I say sorry, that means he wins. If I say sorry, that means I am admitting that I am wrong. If I say sorry, it’s a punishment.

Saying sorry shouldn’t always mean many of these things, and often doesn’t mean any of them. Apologizing can actually be a very good thing. It can be healing, restorative, and peace-giving. If we thoughtlessly resort to it as a quick consequence, we may be losing out on the chance to teach our children more about true repentance, reconciliation and forgiveness.

As you form your own system of consequences, always keep these things in mind:

- What lesson is this teaching them?

- How is it shaping their character?

Consider these scenarios and the hidden messages that might get communicated:

| Consequence | Message Communicated |

| You didn’t clean your room, so now you also have to clean the bathroom. | Helping with household chores is bad (versus encouraging child to help around the house out of responsibility and thoughtfulness). |

| You didn’t pick up your toys, so now you have to give away your toys. | Giving to charity is bad. Plus, one false move and you lose everything (this takes away a child’s sense of control in her life). |

| You didn’t do your homework, so now you have to go to your room and read for an hour. | Reading is something only to be done when you have to (versus encouraging it as a fun and enjoyable leisure activity). |

Finding appropriate and meaningful consequences is one of the hardest pieces for me in this process, and to be honest, I don’t always get it right. Sometimes I just do what’s easy (like temporarily taking something away) rather than spending the time and energy thinking of something that will effectively and meaningfully counter the unwanted behavior. It’s hard to individualize consequences across a class full of children, but I hope to be more thoughtful about this when working with my own children. We won’t always get it right, but being aware that your consequences can have a longer-term and deeper impact is a good first step!

3. Consequences should be realistic and practical things you can and will follow up with

I have heard parents threatening their child with “If you get another warning, I’m gonna cancel the Disneyland trip!” True story. This happened in the middle of a parent-teacher conference.

This was not a good idea. You already bought the tickets. You’re not really going to cancel. Once the kid figures this out, you have undermined your own authority and made your words empty. And if you are going to follow through with it, why should the whole family be punished for one child’s misbehavior?

Futhermore, if the child didn’t know that Disneyland was on the table before they had any behavioral setbacks, it’s unfair and ineffective to drop it on them like that. If they knew ahead of time, at least they could have clearly seen the progression of cause and effect from the start. If you just drop it on them, they will feel very out of control of their lives, and will have little motivation to control their own behavior in the future.

As a sidenote, I also felt that this was unfair to me as the teacher. How could I possibly give a warning now, knowing that it wasn’t the simple “nudge” that I intended it to be, but was actually possibly canceling a family trip? Yikes!

Also, if you choose consequences that are too complicated to carry out, children will pick up on it and might take advantage of the fact that you don’t really want to follow through with it. Think of something realistic, practical, and easy for you to administer. Try to arrange it so the only person feeling the consequences of the action is the child—not you or the whole family.

4. Consequences should happen immediately after the misbehavior

If you have some faraway or abstract punishment, it doesn’t affect them in the present and it won’t impact them the same way. The child needs to be able to see the strong connection between poor choices and consequences, and they need to feel the cause and effect.

For example, students in my class frequently used sports practice as an excuse for incomplete homework. Whenever I mentioned this to their parents, I often heard parents threaten that they would not sign the child up for the next season if the child had any more incomplete homework.

Okay. We found something meaningful to the student: soccer. Check.

We are also communicating that schoolwork takes precedence over extracurricular activities. As a teacher, I can get behind that message. Check.

This is also an action you know you can and will follow up with. Check.

…But this is not the way to do it. First of all, next season as a whole is unrelated to this trimester’s homework. Furthermore, it’s not until next month or next year, so it will feel far away and abstract and not matter very much to the child right now. Even if you did follow through the following year, it is unlikely to affect their immediate behavior and habits.

…But this is not the way to do it. First of all, next season as a whole is unrelated to this trimester’s homework. Furthermore, it’s not until next month or next year, so it will feel far away and abstract and not matter very much to the child right now. Even if you did follow through the following year, it is unlikely to affect their immediate behavior and habits.

Here is a better way to use it. “The next time you have an incomplete assignment, you will have to sit out during soccer practice that evening.” (Yes, even if that means you can’t play in the weekend game.) This hits home, and it hits home now. Avid soccer players probably enjoy practice very much, and the thought of missing practice or sitting on the bench and watching others play is not very fun.

When you ask your child to begin their homework in the next 5 minutes, they might dilly-dally a bit. If you notice they are still watching TV six minutes later and the homework is still not done, try, “I asked you to start your homework five minutes ago. You haven’t started yet, so this is your warning. I want to see you with your homework out in five minutes. Remember, the next consequence is to miss soccer practice.” If they know the next step is losing out on practice, and if they know you will not hesitate to follow through, I would guess that five minutes later, homework will be out.

Meaningful, thoughtful, realistic/practical, and immediate.

Good luck!

I hope you have picked up a concept or two (or a whole system) that you find helpful in steering your children toward better behavior. I believe it is our job to train our children up with the tools to be able to control themselves as needed. While outward behavior is not necessarily any indicator of character, intentionally shaping it is one way we can help our children develop and grow.

(I know it was long: THANK YOU FOR READING!!!)

Too hard? Here’s an easier system to try: An Alternative (and Easier) System of Consequences.

This post is part of my series on How to Shape Children’s Behavior.

—————————–

Related Posts:

How to Shape Children’s Behavior

Preventing Misbehavior: What Every Parent Should Know

Using Rewards Strategically to Shape Behavior

I really enjoyed reading this! The comparison of Punishment vs Consequence is spot-on. I’d like to add that meaningful consequences should be used in conjunction with positive reinforcement where you actively catch the child doing something good. Setting clear expectations and highlighting (dare I say rewarding, even if that reward is simply adult attention) the positive behavior works to encourage the child to pursue more of these behaviors, while concurrently, the graduated consequences will remind them to decrease negative behaviors. Too much attention on negatives can backfire with some kids who will take any attention they can get, even negative consequences. Pointing to the positives should precede any introduction of a consequence system. Together, they are pretty powerful catalysts of behavioral change.

I totally agree that it’s important to set clear expectations and concurrently reward the child for behaviors you want to see (even if it’s just attention :)). Not sure if you’ve seen it, but I also shared some of my thoughts on those topics (linked).

Thanks so much for your posts!

Several ones about behavior actually made me want to try to work on my own behavior, mostly for the sake of my couple. And I will start with a single first goal. 🙂 (“one thing at a time”)

… you wouldn’t, by any chance, have advice for adapting the behaviour shaping to a spouse? 😀

Thanks for dropping a nice comment! Thanks also for reading along! I really appreciate it.

Actually, I have quite a few thoughts on marriage, too. I wanna wrap up some of these children-related posts first, but I am gonna get right on that in the next couple of months! I wouldn’t necessarily call it behavior-shaping for spouses… but I wouldn’t be surprised if following through with some of these ideas ended up in changing the behavior of both you and your spouse for the better =).

Not sure how I found your site but I like it. So, here’s a scenario that happened a long time ago and I’ve always wondered how it could have been done better. A friend of mine in high school was punished and the consequence was not going to a school dance. Here’s the kicker. He was asked by a girl. By the time he got his consequence of not being able to go, it was to late for the girl who asked him to find another date. So, not only did it ruin his night, but it drastically affected her too. He really liked the girl so the consequence really whipped him into shape later, but in the moment it really messed up the girl’s planned evening too. Thoughts?

I think a lot depends on that specific situation: did he know that the school dance was on the line when he made a poor choice? Did he even make a poor choice, or was it just a mistake? I think it’s especially unfair if punishments are dropped on people out of nowhere. But if he knew about this consequence and chose to put the dance at risk, then that’s part of his choice. I really don’t know the situation, so I’m not really sure what I think about it.

For children who continue to make poor choices, I do think it’s an important lesson for them to see that their poor choices can drastically affect others. For a child who is always yelling out the answers in class, I need them to see that this robs their classmates of the opportunity not only to get in an answer or two, but to even THINK. So I do think that sometimes, part of the consequence is seeing how others suffer because of your actions, too. Children (and teenagers and adults) need to see how their poor choices can affect everyone around them, and maybe a school dance is a relatively harmless way of teaching that lesson. The consequences of our poor choices only get weightier as we grow up and become responsible for more. That’s really too bad for the girl, though :(. That kind of thing is a huge deal in high school!

I am struggling with encouraging good behavior and figuring out consequences for my 4-year-old son. One behavior we’re trying to work on with him is politeness and friendliness. He says he feels shy a lot, which can manifest itself as rudeness (he will sometimes say “no!” to parents of friends) and unfriendliness (blocking other kids at the playground, when I think he’s actually trying to connect). I find it challenging to handle because I’m often not right there (and shouldn’t be really) and don’t want to force him to be extroverted, but do want him to show basic politeness and friendliness with others. Thoughts?

Aw, I can imagine that’s hard for you to watch :(. I’m not really sure how to handle that situation, especially since you don’t want to be hovering for all his social interactions. Hopefully others will have some ideas for that age group!

Has he always been shy? Or has this behaviour come on recently. Has he got to deal with more complex situations than he is used to? A new sibling ? A new area?

Anyway I think you should cut him some slack. Of my three children two were more extrovert but the third was introvert and very shy. It took me a while to understand how different his approach was to the world. He really didn’t like new situations but when he was confident he was able to engage fully.

Also I think can be OK to say NO to an adult …it depends on the situation and on the whole I would rather my child said no if they felt unsure or uneasy about something. But it is useful to teach him how to say no.

SO what can you do. I suggest giving him positive feedback when he gets it right rather than worrying when he gets it wrong.

I think family board games are very good for instilling social confidence , you can loose or win but you take part and have turn and there are lots of opportunities for conversation and there are rules.

Social situations and making friends in the playground really are hard skills to learn . One thing you can do is make sure he is happy and confident the rest of the time and gradually this will spill over into his social interactions outside home.

You cant give him all your social knowledge in one go so I suggest working on one bit of those complex interactions at a time.

You need opportunities to practice making new friends and at least getting along with people , this can come with a music group or sports or arts activities or just the things you do as a family

Some kids take longer to be socially confident than others. Give him time to be himself. Was his Dad or another member of the family a shy kid too?

I dont think this is about consequences, after all if he block other kids the consequence is already inbuilt in the situation , he has lost the opportunity for friendship. If he says no to an adult he has lost the opportunity to be engaged in what is going on.

its about confidence and social awareness.

So I have the privilege of watching twin 6 year olds over the summer. Great kids! One is a. Adorable artistic and theatrical girl who definitely stops at a warning glance, her brother on the other hand is a 5-2. A little genius at that. His academic mind is a full grade ahead, and his social skills are a full year behind. She learns by watching him smack into consequences all the time and then tries to help by telling him to behave, and occasionally chastises him when she was admittedly right.

He on the other hand somehow forgot the install switch for verbal filters or reading any kind of warning, let alone leaping before he looks in almost any situation, which tends to get him injured more. When he does smack into the consequences it’s the end of the world and he spends a good deal of time trying to hug or kiss to make it better instead of processing a behavior change. I’m gonna try what you have mentioned here, but if you had any additional suggestions, it would be appreciated.

Ooh good luck! One thing to consider is that he might pull the “this isn’t fair” card on you if he’s getting consequences and she isn’t, so when initially setting things up, you can mention that it applies to both children. It will probably just so happen that he will end up receiving more than she does, but at least he’ll know that it’s because of his own poor choices… and not because his sister is somehow exempt from consequences, but just that she has made better choices.

If you try a system of rewards (https://cuppacocoa.com/using-rewards-strategically-to-shape-behavior/) you might also want to have a little chat with her beforehand and explain that it’s great that she knows how to behave well, but that her brother needs a little extra help and so you’re going to be doing a system of rewards with him. If you don’t have this personal chat beforehand, she might feel like it’s not fair that she’s always behaving well, yet he gets rewards for small things. You might consider giving her something new to work towards, too, like helping with a certain chore, so she can also earn rewards.